At MYOB we’ve been improving our graduate programme for software developers. Today I would like to share some of the insights we’ve gained over the last few years around a practice I call technical mentorship.

Some background

For the last two years I’ve been guiding our graduate software developer academy at MYOB. The academy is where we employ less experienced software practitioners and through a structured learning and mentorship programme intentionally grow their capability. I cover a bit around the evolution of the structure of the programme in a previous post. In this post I’m going to share some insights I’ve gained around a form of mentorship I call technical mentorship.

Mentoring software developers

Mentoring is a great way to grow software developers. From what I’ve seen, I don’t believe our graduates would learn and grow as effectively as they do if we didn’t have amazing dedicated mentors. So why is it so powerful? Three attributes that immediately come to mind are context, timing and human connection.

Context is essential for us to learn effectively. Understanding why we are learning what we are learning is important for us to remember it. Many other forms of learning (blogs, books, online tutorials) can tell us why in general something is important but aren’t able to understand our specific context and relate it back to us. Mentors are able to understand and give context.

Timing is just as important as context. Our brains are wired to forget things, especially if they are not relevant to what we are doing right now. Great mentors focus on things relevant to our current challenges.

Human connection. We learn best through social interactions from people we feel connected to. Mentoring done right forms a human connection between mentor and mentee that enhances the growth experience.

The ellusive definition

As I discovered early on, the word mentor/mentoring is a loaded word. It means vastly different things to different people. If you read the definition on Wikipedia it says: “Mentoring is a process that always involves communication and is relationship-based, but its precise definition is elusive.”.

Mentoring(s)… precise definition is elusive

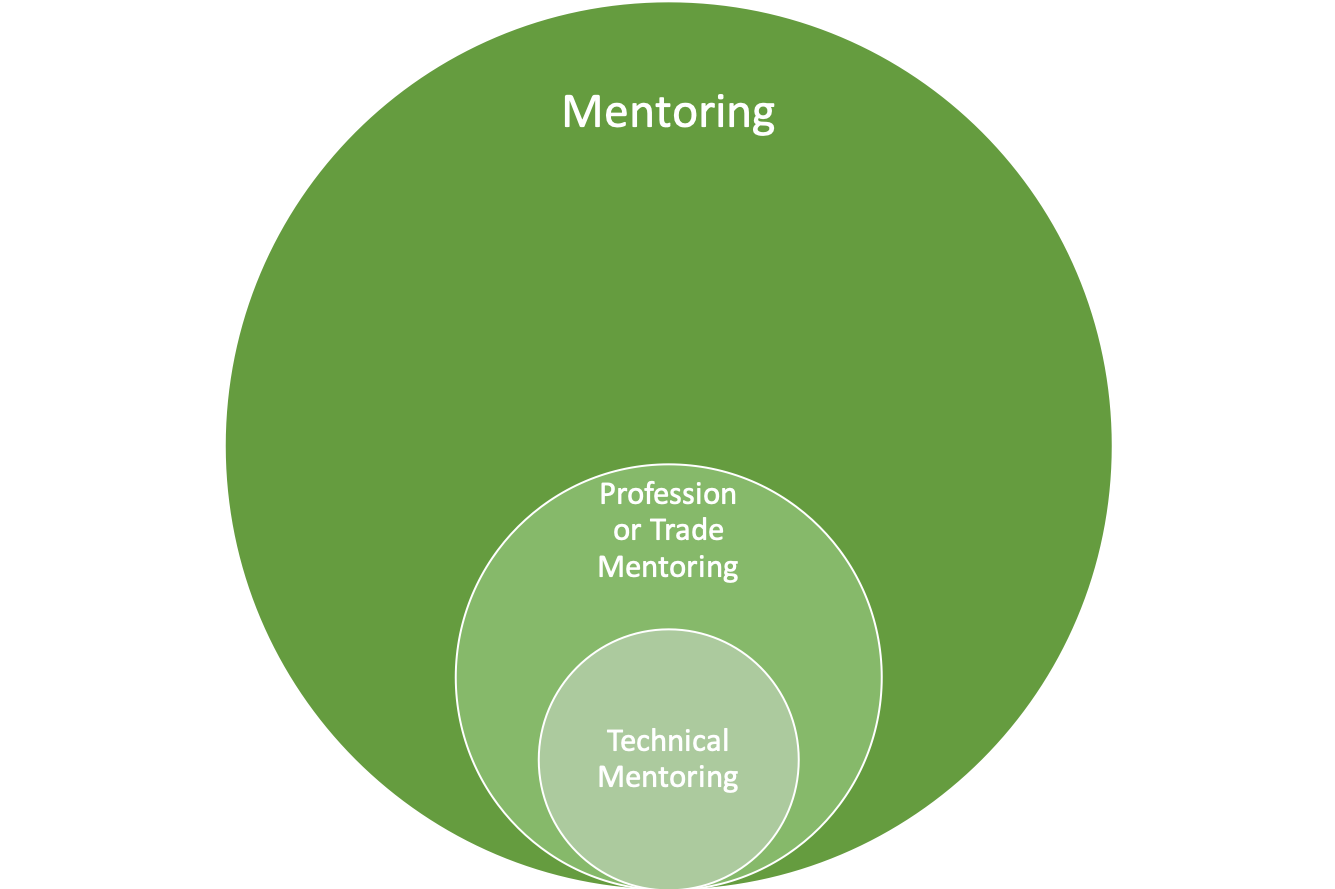

I fully agree. The precise definition of mentoring is elusive! Turns out, going back to Wikipedia you discover numerous different strains of mentoring all with their own unique names and attributes.

Looking at these various strains of mentoring, what we do with our graduate software developer is a form of profession or trade mentoring. As Wikipedia explains: A profession or trade mentor is someone who is currently in the profession the mentee is entering. That person knows the trends, important changes and new practices that the mentee should know to stay at the top of their career and helps guide them through these things.

Unfortunately I don’t like the phrases profession mentoring or trade mentoring, so I’m going to create a subset of mentoring specific to software developers, I call it technical mentoring (gasp and drum roll at the same time).

What is technical mentoring?

So what is technical mentoring? Let me propose a definition…

Technical mentoring is a process for the informal transmission of knowledge, skills, and support perceived by the recipient as relevant to their development as a software professional; it entails informal communication, usually face-to-face and during a sustained period of time, between the person who is perceived to have greater relevant knowledge, wisdom, and technical skills (the mentor) and a person who is perceived to have less (the protégé)”*.

Technical mentoring is a process for the informal transmission of knowledge, skills, and support between the mentor and the protege relevant to their development as a software professional

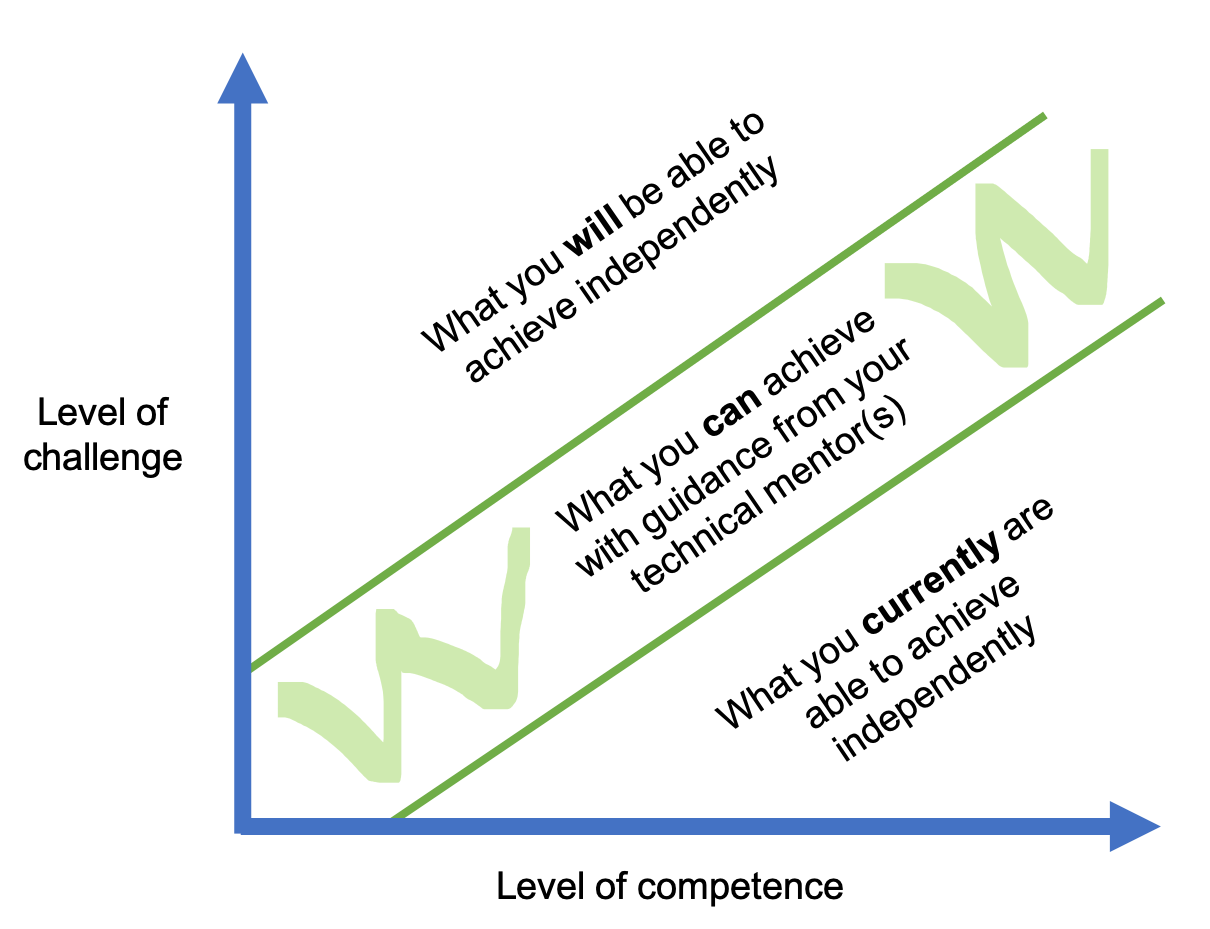

One way to visually represent what technical mentoring helps achieve is the following diagram which is an adaption of Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development.

Vygotsky’s work is used largely in the development of cognition for children however I believe it translates well to growing software developers. Let me explain.

There are a set of things you are comfortable doing independently, and a set of things that are beyond your current abilities. Somewhere between those two areas is a zone (which he calls the Zone of Proximal Development or ZPD) where if guided by a more knowledgeable other you are able operate and perform. This is where your technical mentor fits in, your mentor is there to help you get into the ZPD and while there guide you using various mentoring tools and techniques. With time and practice you learn and develop and are able to do more challenging work independently.

Technical mentoring is a role, not a technique

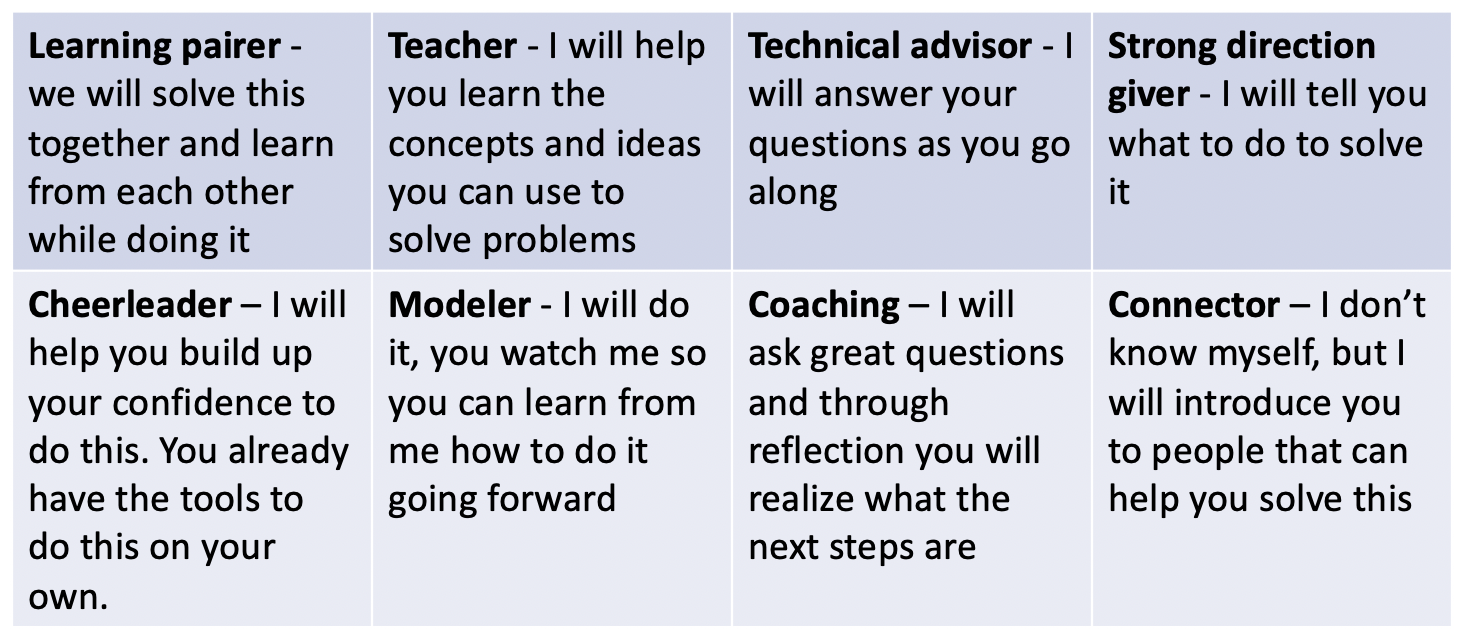

Technical mentorship is a role, not a technique. Let me attempt to explain the difference. The English language is clumsy, we often use the same words to describe both roles and techniques. For example, “coaching” is a role and a technique. If you are the coach of a soccer team and are “coaching” them, that is your performing your role; if you are coaching someone through making a difficult decision, that’s a technique you are using to help achieve an outcome (them gaining insights to make a decision by you asking probing questions). Technical mentorship is a role.

There are are various techniques technical mentors use to be effective. Which technique you use when mentoring largely depends on your experience and where your mentee is at in their learning journey.

Some of the techniques I’ve seen include:

How do we get better at it

So how do we get better at it? I going to share a handful of things I’ve learned over the last two years. I am going to focus around things specifically for technical mentoring in the graduate developer space, I’ve made a separate post around things you can do to get better at mentoring in general.

Adjust your approach depending on their skill level

The first thing I’ve learned is you need to adjust your approach depending on your mentee’s skill level. The nature of how someone is mentored changes as they grow in experience and capability. The Dreyfus model of skills acquisition is a useful model to use when figuring out what approach you need to take.

Generally, in most technical capabilities graduate software developers are at the Novice or Advanced Beginner stage of Dreyfus. That means when mentoring a grad you are going to focus on providing them detailed step by step instructions or simple projects in a safe to fail environment. We’ve found the use of coding katas (synthetic coding problems) and group projects useful. I go through both of these later in this post.

Put together a roadmap

The next thing I want to share is put together a roadmap. I learned this from a colleague, John Contad who is someone I consider an expert at technical mentorship.

How do you do it? One way is to ask what role your mentee is aiming for next. Once you have identified that you can work together to identify the capabilities someone applying for that role needs to have to start out. Next, you identify their current capabilities. This should give a delta.

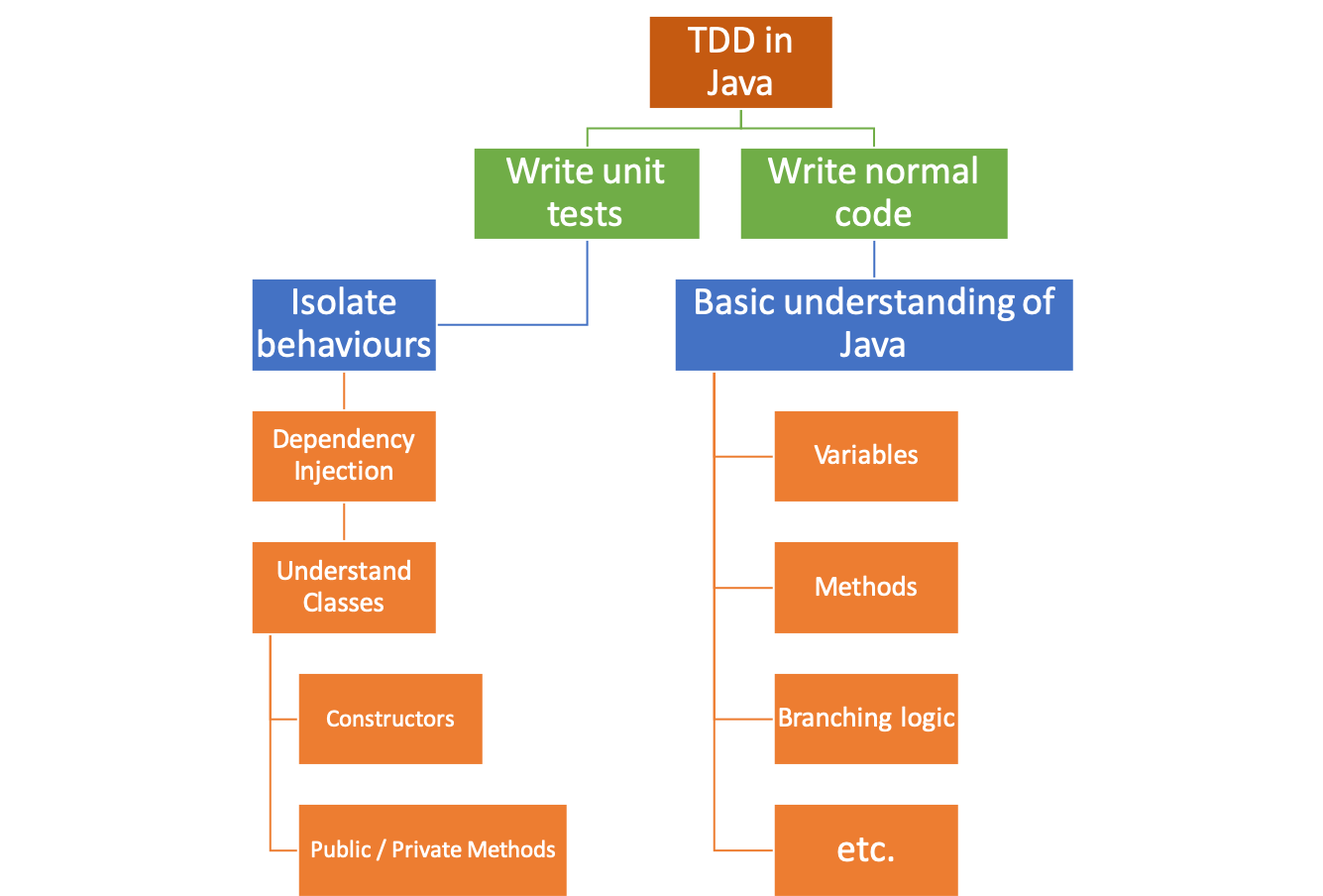

Looking at the delta, pick a capability that you can help your grad with. Break that capability into all the little bits of information they need to have to perform that capability. Map these pieces of information into a dependency tree. Starting at the bottom and working your way up the tree you now have a roadmap.

Make sure your grad understands and buys into the roadmap and understands why certain things are there. As humans for us to remember things we need to understand why else we forget it very quickly.

Learn how to effectively teach skills

The second tip I want to share is learn how to effectively teach skills. I once heard someone trying to mentor a grad say… I can’t do that, that’s teaching. I’m their mentor, not their teacher! While there isn’t a one to one mapping between technical mentoring and teaching, often you need to leverage teaching as a tool especially if you are mentoring someone at a novice or advanced beginner level.

Now, for many of us you have an image locked in your head of what it means to be a teacher. I went to school in the 80’s and 90’s and teachers in those days were people that stood at the front of the class who talked a lot and wrote things on a chalk board. That’s not the type of teaching I’m referring to!

Instead, I’m referring to teaching skills. Investing a bit of time into understanding the psychology behind teaching skills goes a long way to helping you effectively mentor someone. Now, you don’t have to go to university to develop your teaching skills. There are a handful of models I’ve found useful to guide how I teach. I’m going to share a few of them below.

Blooms Taxonomy of Learning Model

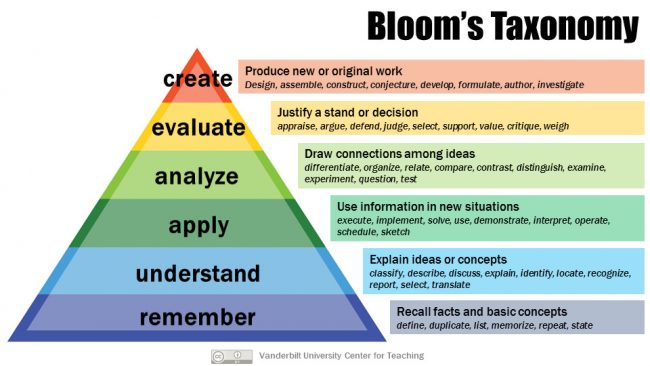

I found Blooms Taxonomy of Learning a useful model. Bloom is a hierarchical ordering of cognitive skills that can a help mentors teach better. It looks as follows:

By hierarchical I mean you need to work your way up from rememeber to create. For example, you need to be able to recall facts and basic concepts first, following that you should be able to explain ideas or concepts, following that apply them and so on until you get to create where you are at a cognitive level of being able to produce new or original work.

How does this help you mentor more effectively? First, it gives you an order of progression or plan of attack when approaching a new technical concept.

For example, if you were helping your grad learn a new programming language, you would start with activities that help them remember. This would include things like being able to recall the syntax for declaring a method, defining a varaible, passing parameters and so on.

Only once your grad has passed the knowledge stage for the basic syntax should you focus on understanding. Do they understand why methods are useful? Why would we need varaiables? Why would we use looping constructs? And so on.

Only once you have a solid knowledge does it make sense to move on to apply. Let’s solve a simple problem using the things we have learned so far. And so on…

Thinking in terms of Bloom’s different levels allows you to have a structured approach in teaching and I’ve found it extremely useful. For instance, it may be unproductive to ask someone to debug an issue in a system without them first having passed the “apply” stage for the technology that it’s been developed in.

Use direct instruction to develop your grads skills

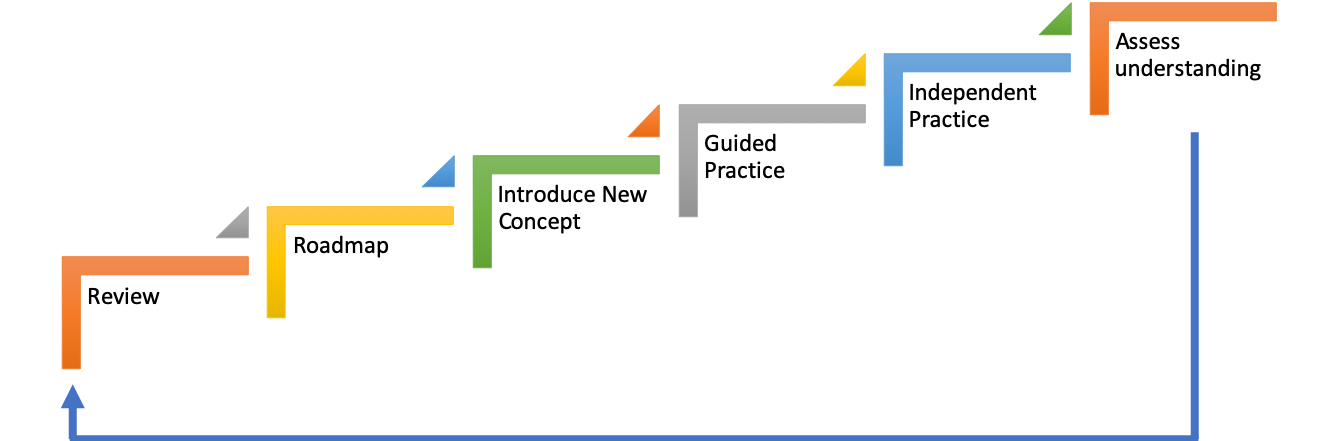

The last technique around teaching I want to mention is that of Direct instruction. Direct instruction is a structured sequenced approach. Teachers often use it to help someone learn a concept. Mentors can use it to help somone develop a skill. I’ve seen different patterns or variations on the internet but the one I find most useful in the software world looks as follows:

Let me use an example of how you would use this pattern to learning a skill like Test Driven Development.

Step 1 - Review - First, start by reviewing what your grad has covered so far. Taking my example of “TDD in Java” above (under roadmap). We would review all the dependent information…writing a unit test (dependency injection, understanding classes) and writing normal code (basic understanding of java).

Step 2 - Roadmap - Next we go to roadmap. TDD in Java is next on the roadmap.

Step 3 - Introduce new concept - Then, you introduce the concept. What are the benefits of TDD, why do we do it. What is the theory behind it. Red, Green, Refactory circle.

Step 4 - Guided practice - You then move into guided practice. You may start off using pair programming as a tool to help guided practice. I would normally start by “driving” and walking through a very simple problem. Maybe a coding kata like string calculator kata. At some point in working through the problem I would ask my grad to go behind the keyboard and “drive”. We may do one kata together, or several.

Step 5 - Independent practice - Next, get your grad to work through a similar coding kata on their own. You may get them to redo the same problem. But without your help or work through a similar problem that is focussing on the same skill (TDD).

Step 6 - Assess understanding - Once they have done their independent practice, as the mentor it’s now up to you to assess their understanding. I would probably take pick a new problem and pair on it with them again but this time have them at the keyboard and me largely observing. We may go to the whiteboard and have them explain the concept to me. Draw out the approach they are taking and so on.

Step 7 - Go back to review - Once you are finished assessing understanding you make a call if they understand a concept properly, or if you can move on to the next step in your roadmap. For all intents and purposes you are back to review.

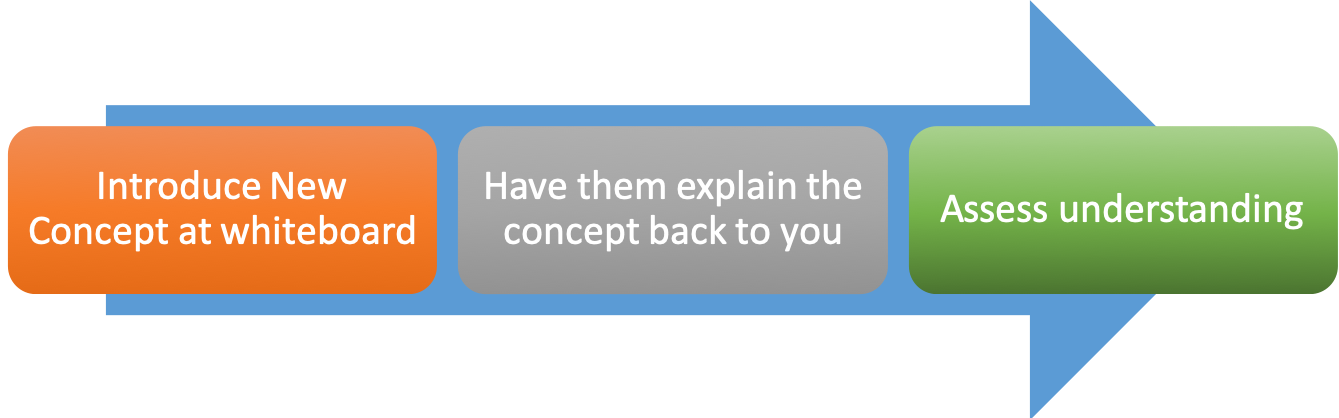

Have them explain it on a whiteboard first

I used to think the best way to learn how to code is to go straight to your ide and code something. My thoughts on this are evolving. Yes, there may be some benefit in doing this to learn basic concepts like syntax but I belive there is a better way.

I’m seeing huge benefits in first explaining and drawing out an approach at the whiteboard. I believe this helps form a high level or conceptual view of the workAlso, the more I learn about how human memory works the more I realize how visual forms of information are the most powerful forms for recall.

Personally, I’m not very skilled at explaining things at a whiteboard yet which is probably why initially I undervalued it and went straight to coding. This is now an area I’m looking to personally grow in.

Pair programming is a powerful way to transfer knowledge

Pair programming is a powerful way to transfer knowledge. I’ve mentioned it already as a tool to use at various levels of direct instruction.

While how you do pairing depends on whether you are going through a guided practice or assessing understanding one general comment around pairing is inexperienced mentors tend to type at the keyboard too much. In most situations, if you are going pair have your mentee at the keyboard. Having your mentee typing things makes the pairing activity experiential. Experiential learning energizes and enhances the learning experience.

Should you pair all the time? Absolutely not. There is huge value in your grad having independent practice. Look for a balance between pairing and independent practice.

Coding katas or synthetic problems

Kata, originally a Japanese word, is a series of detailed choreographed patterns of movements practiced either solo or in pairs to teach proven techniques and practice in martial arts.

A code kata is a programming problem suitable for practicing specific programming patterns found in software development. Think of it as a synthetic problem to practice a technique on. The concept of a code kata was first popularized by Dave Thomas, co-author of the book The Pragmatic Programmer.

I’ve found huge value in code katas with a very gotchas. Let’s spend some time on what’s good about them first.

Katas help you focus on a specific thing by removing the noise or redundant information around the problem. Noise would be anything outside the learning objective. So for example, if you were learning how to do object composition in your back end code, noise would be if you had a UI framework like React in the same problem. Reducing noise or redundant information is a recommended practice for improving the learning experience in cognitive load theory as it get’s you to the core of what you are learning.

There are some challenges in using code katas to help mentor software grads. The one challenge with a code kata is you need to clearly link it to value. What is the value your graduate is getting from doing it. Similar to what happened with the karate kid where he never connected Mr Miyagis wax on wax off work to how it would improve his karate, if you haven’t linked the thing your graduate is learning in the code kata to why this will help them be a better software developer their brain is going to forget it really quickly.

Motivation

The other big challenge with code katas is staying motivated. Because they are toy problems they don’t solve any business need and don’t add any value to the organization. A big driver for motivation is to add value to where you work. This is particularly strong in most graduate software developers I’ve worked with.

Because katas add no value, the graduates motivation to keep working through a kata quickly wanes. Dan Ariely does a great TED Talk on motivation where he shares an experiment around measuring motivation for people doing drawings. I’m not going to go into the details here other than to suggest that if you are going to use code katas as a learning mechanism make sure to reviewing the work thoroughly and give detailed feedback to your graduate once they have completed it. This increases their motivation to do it again.

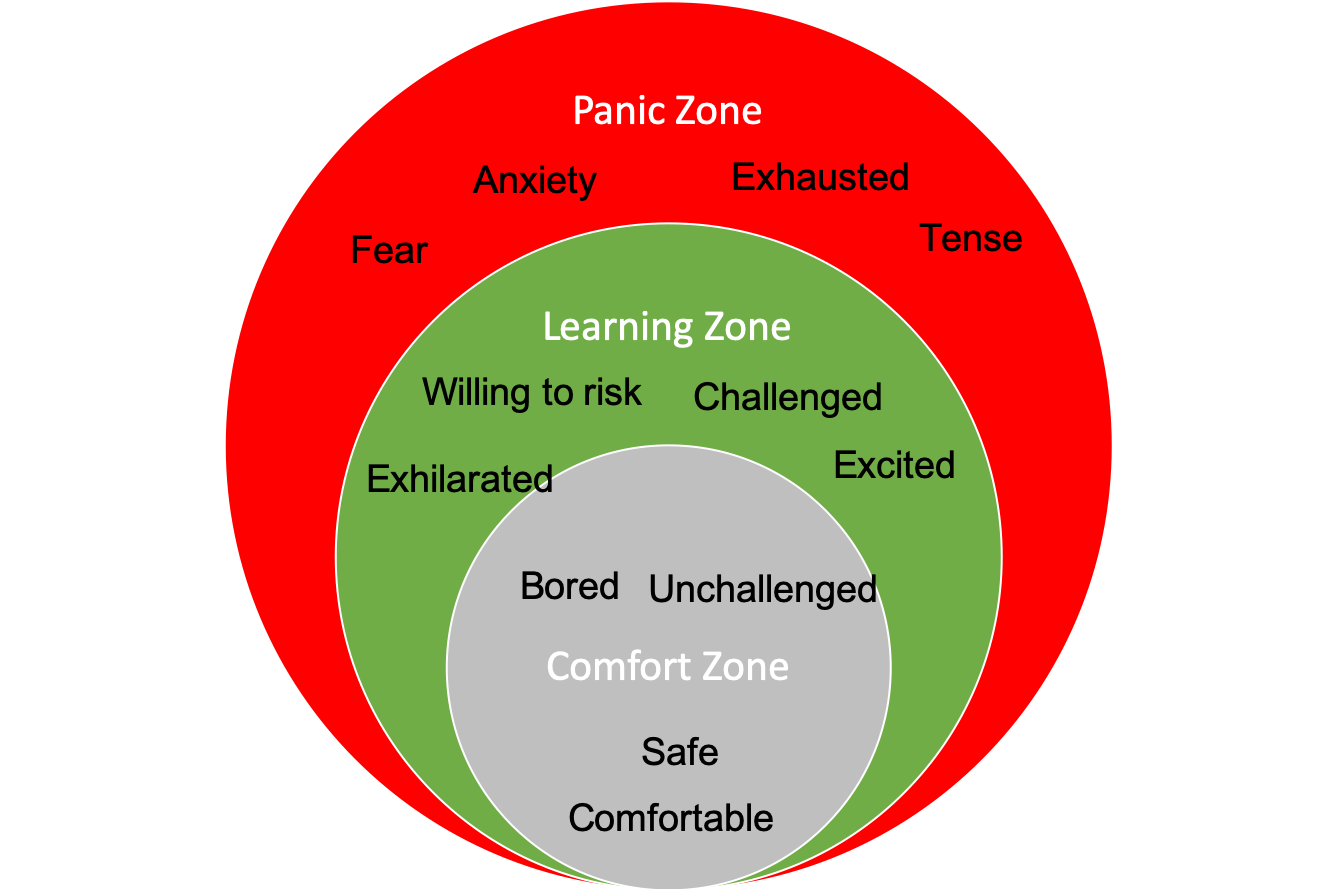

Another way to keep tabs on motivation is to use something like Senninger’s learning zone model. This can be used as a tool to identify if your grad is in the sweet spot for learning or if their motivation is decreasing.

In Senningers model there are three zones, comfort, learning and panic. The ideal is to have your grad in the “learning zone”, in this zone learning is at its optimal. Whenever you do a kata ask your grad to indicate in which of the three zones they feel they are in.

If they say they have feelings of boredom, being comfortable, or being unchallenged it’s an indication they are in the comfort zone. If this is the case you need to determine if they in the comfort zone because they are bored of the problem (but still need to develop the skill) or if they have actually developed the skill and it’s fine moving onto the next item in your roadmap. If they are bored with the problem, look for a new kata that exercises the same skills.

Senningers model is also useful for gauging if a piece of work is going to stretch them too much. In the panic zone someone has feelings of anxiety, fear, exhaustion or tenseness. Being in the fear zone is not a good place because you don’t learn much. If your grad is having feelings like this it is an indication that you may be stretching them too much.

Quorum Reviews

Another tool we have seen help address motivation is leveraging something we call quorum reviews. A quorum review is similar to a group code review. Essentially, a graduate presents a piece of work to a wider group of people for feedback. In our quorum reviews we have at least 5 people in a review. The graduate, their two mentors (we work in a co-mentorship model), two other peers and a technical lead.

We invest time in each quorum review. A review usually takes between 45 minutes and to an hour and a half. After introducing quorum reviews we’ve seen a significant increase in motivation of the graduate.

The challenge with a quorum review is getting the timing and environment right. If you do a quorum review before your graduate is ready you can push them into panic mode. Likewise, if you have people in the review that your graduate is intimidated by, back into panic mode they go.

To counter these we intentionally introduce graduates to everyone that they will be in their review well in advance to the review happening and do plenty of dry runs so that by the time the review occurs the graduate is comfortable with the process.

Building Meaningful Systems

The last tool I want to spend time on today is building meaningful systems. I’ve seen huge value in having our graduates build meaningful systems.

Bringing this back to Dreyfus’s model, meaningful systems are complex but controlled projects that give real world exposure. Let me highlight, there is a difference between a client facing production system and a meaningful system appropriate for your graduate to build. A client facing production system is not a safe place to fail.

In our programme we have our graduates build all the internal tools we use for managing the programme. These tools have a massive impact on my life (when they work they save me a ton of time) but if they don’t work it isn’t the end of the world. I understand. Graduates love building them because they learn a ton and they see it as adding value.

The challenge we’ve seen with building meaningful systems is they have a lot of complexity and can have unnecessary noise. Identifying upfront what you want your graduate to learn through building the system is important. If you do this you can reduce the noise by treating some areas of the system as a “black box” for your graduate. Something you’ve gotten working for them which is unnecessary for them to understand at this point in time.

These are some of tools we use now, there are more…

So with that, I’ve covered some of the tools we use to mentor our graduates. I don’t believe there is one correct way mentor graduates. I’m interested in learning what others are doing.

With that I want to end off with one last insight. If we go back to Blooms taxonomy of learning I mentioned there were different stages in the learning process. In the process of mentoring someone else you are drawing connections between different ideas, justifying a stand or decision and so on. On Blooms taxonomy these are the analyze and evaluate stages. In many ways as a mentor, you are growing the most. In being able to mentor someone else you are in effect improving your own skills so that you can produce new or original work.

Going back to blooms… mentoring reinforces your own learning and growth to ultimately help you produce new or original work.

It gives meaning to life, having an impact on someone else can be an extremely fulfilling experience.

Would love to have your insights.